I was asked in a recent conversation I had with a new friend, “How do you find stories about your ancestors when you haven’t inherited any stories?” I’m afraid the answer is “You have to write them.” The best place to start is at the local history room in your public library. All libraries, including public, university, and state libraries, have a local history collection. In a county branch, the collection might be a shelf or two or a small corner. In a city library, there is often an entire room reserved for genealogy and local history, while a university library might have half a wing dedicated to the subject.

The Knoxville Public Library system has such an extensive collection of local history and genealogy that it is housed in its own building! Behold, the Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection takes up the entire fourth floor of the East Tennessee History Center.

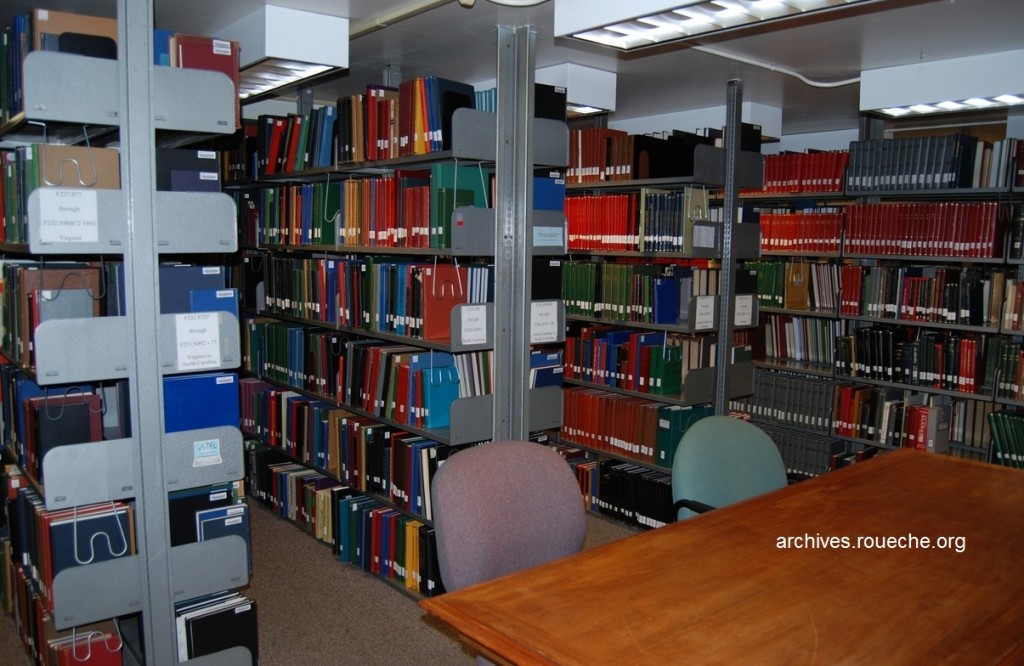

The McClung Collection is located at 601 So. Gay St. in Knoxville. This picture shows about 1/4 of the room and there is another room beyond and more services and resources than I can list!

A local history collection usually includes volumes that pertain to all of the states that border the library’s home state. This is to allow the researcher to do much of their study in one location, even when they are researching an era when borders had shifted. It also allows him to cover an ancestral family’s migration journey without having to recreate the trip by car! At the Tennessee State Library and Archives, this means they have family histories and state and county history books for eight states!

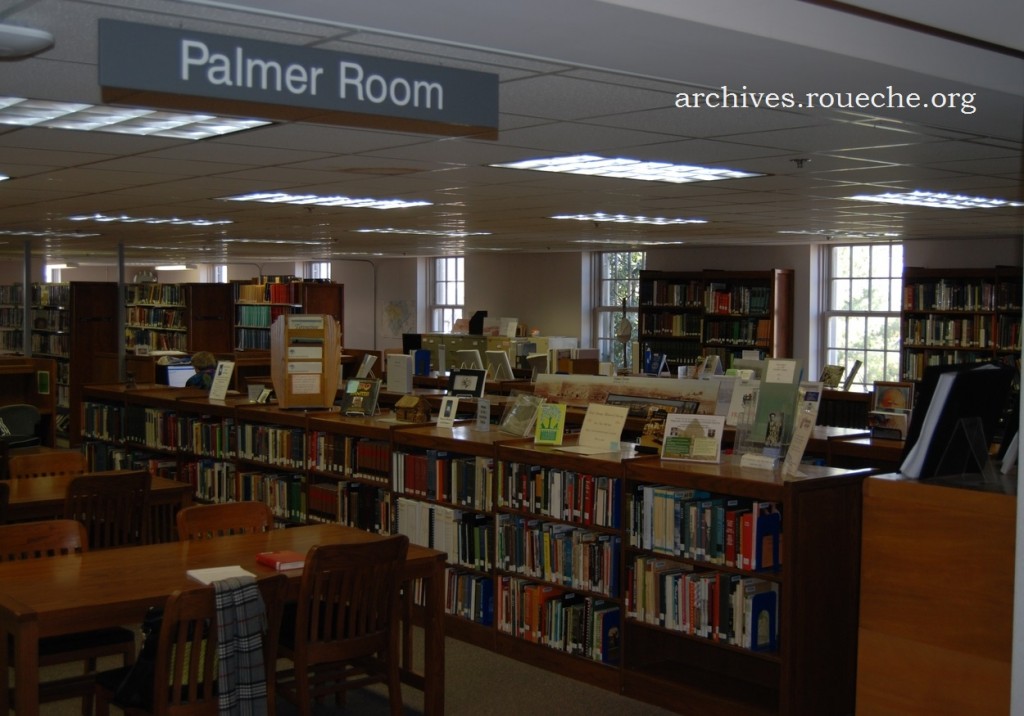

Family history narratives at TSLA are in one room while the county and state histories are in the main reading room.

Of course, the grandaddy of local history libraries is the Allen County Library in Fort Wayne, Indiana. From the mid-1930s to the early 1960s, librarians Rex Potterf, and his successor Fred Reynolds, began actively collecting genealogical books and journals, local history texts and quarterlies, for Indiana and much of the Mid-West, rather than waiting for books to be donated. They shared a “If you build it, they will come,” philosophy that gave birth to the marvelous collection at Allen County, today. It is a facility that celebrates genealogists and inspired Rick J. Ashton to refer to it as “How the Public Library became the Only Tourist Attraction in Fort Wayne, Indiana.” One of these days, I am going there.

My mother’s paternal lines are from Virginia, so even though I live in Tennessee, this means that my local Kingsport Public Library just might have something to aid me in my research. Surnames like Armstrong, Blanton, Southworth, and Stevens are on my list.

To Start: Before you leave home, make a list of search terms. This list should consist of surnames, county names, and city names. Don’t just list your direct surnames, include the lines that have married into your mainlines. (I recommend using an online tool to help you track the names of counties and towns as they can change over the years. For Virginia, I use Wikipedia’s List of Counties for Virginia. It includes a map, an alphabetical list of 95 counties and their name origins and dates established. As you go back in time, your ancestor’s may not have moved, but their county borders may have!)

Use the Catalog: Enter your search terms into the online catalog for your library and make a list of possible volumes that might include historical background for any of your research interests.

Ask a Librarian: Consult your local history librarian. He or she is the caretaker of that collection and can recommend resources you may not have found in your own search, give you tips on where to look next, and, with a little notice, just might be able to track down a thing or two for you or connect you with a fellow researcher or genealogy group.

Take Note: When you read a county history, take notes on what you learn about the economy, the geography, the religious and cultural traditions, and industry of the area. All of these inform you about your ancestor’s life. Next, use the index of each volume and see if it includes any of your surnames. Finding even one of the names in a book means that effort was worth it.

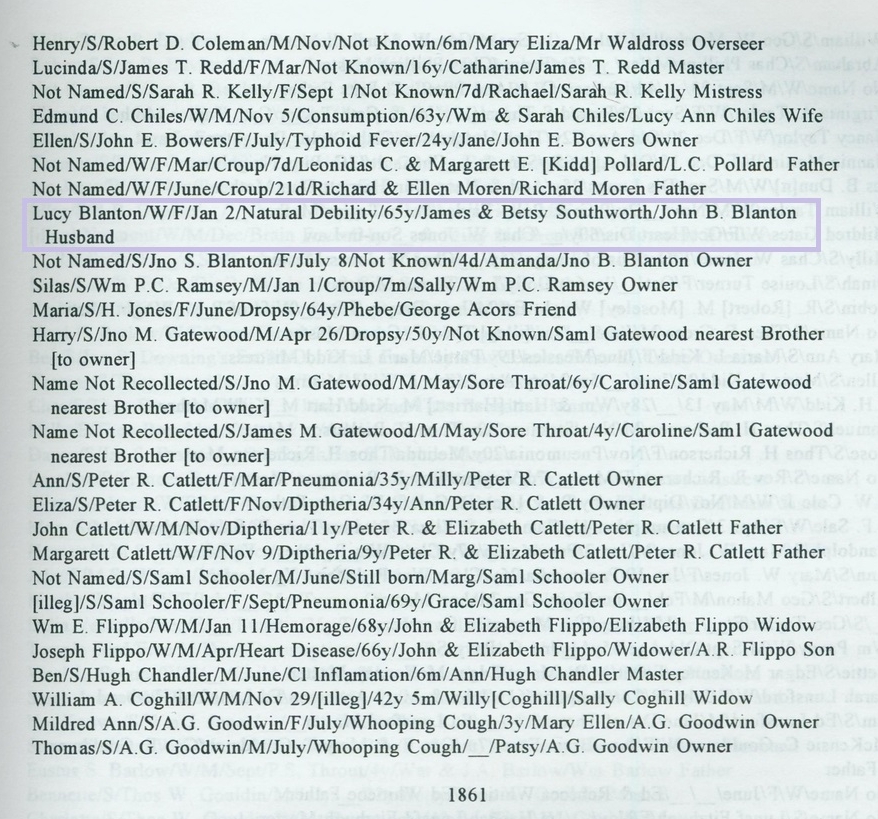

I will share with you my adventures from just one afternoon at my local history reading room. I found the book Caroline County, Virginia, Bureau of Vital Statistics Death Records, 1853-1896, edited by H.R.Collins, 1999, during my online catalog search. It is a transcription of county records. What a story it had to tell. Not only was I able to add names to my pedigree chart and to fill in missing dates, but I was able to discern whether they owned land, how they were employed, and, sadly, if they owned slaves. Even though some of these records have been digitized, being able to see four decades of death reports for an entire county in one sitting paints a picture of the economy, disease patterns, medical knowledge, and political and social changes. These details can definitely give the family historian something to write about.

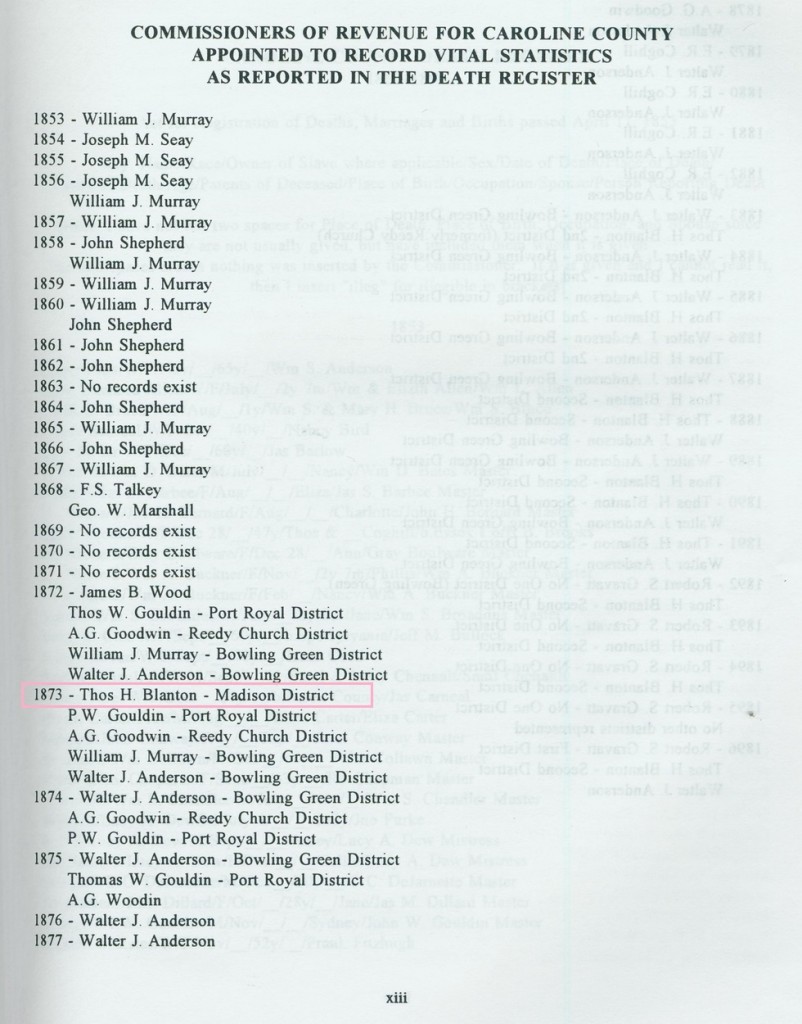

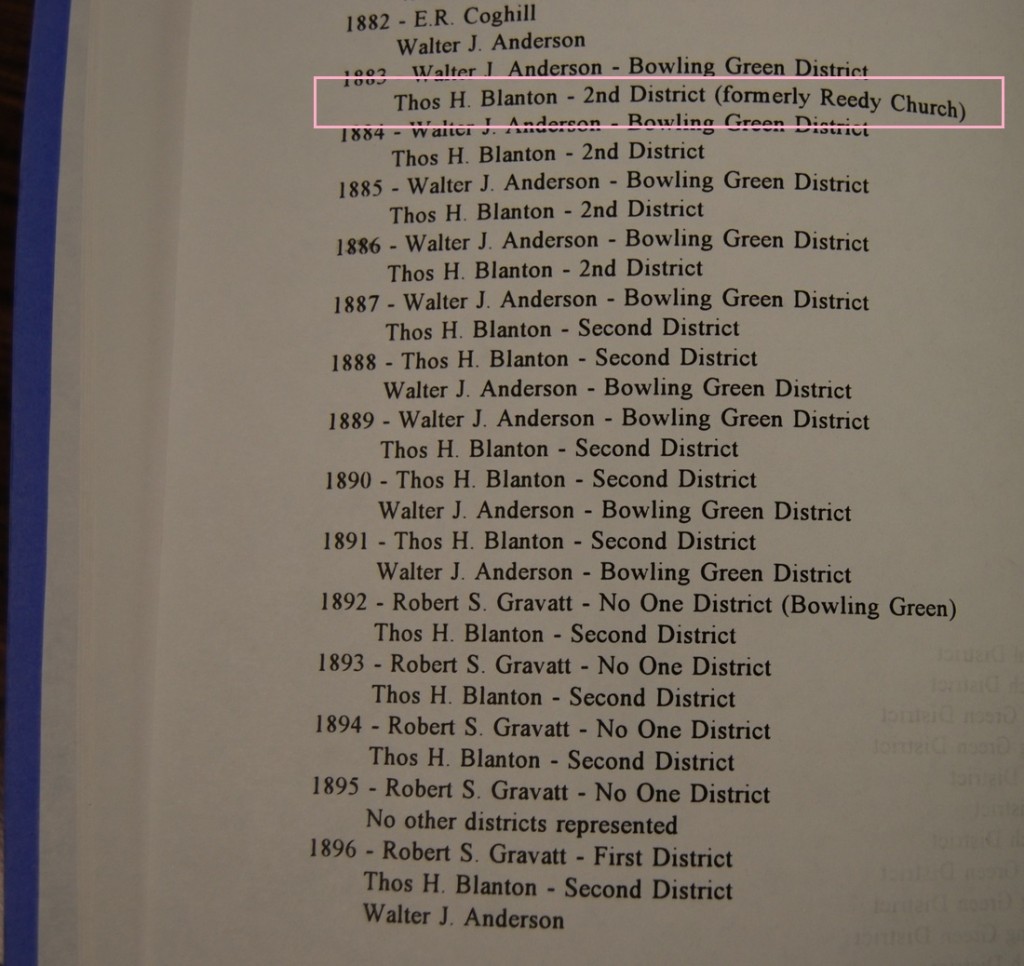

In the front of the book, the editor included three things. 1. a legend to help the reader understand the entries, 2. a list of the men who recorded the entries, 3. a list of all of the causes of death recorded during the 43-year span (fascinating).

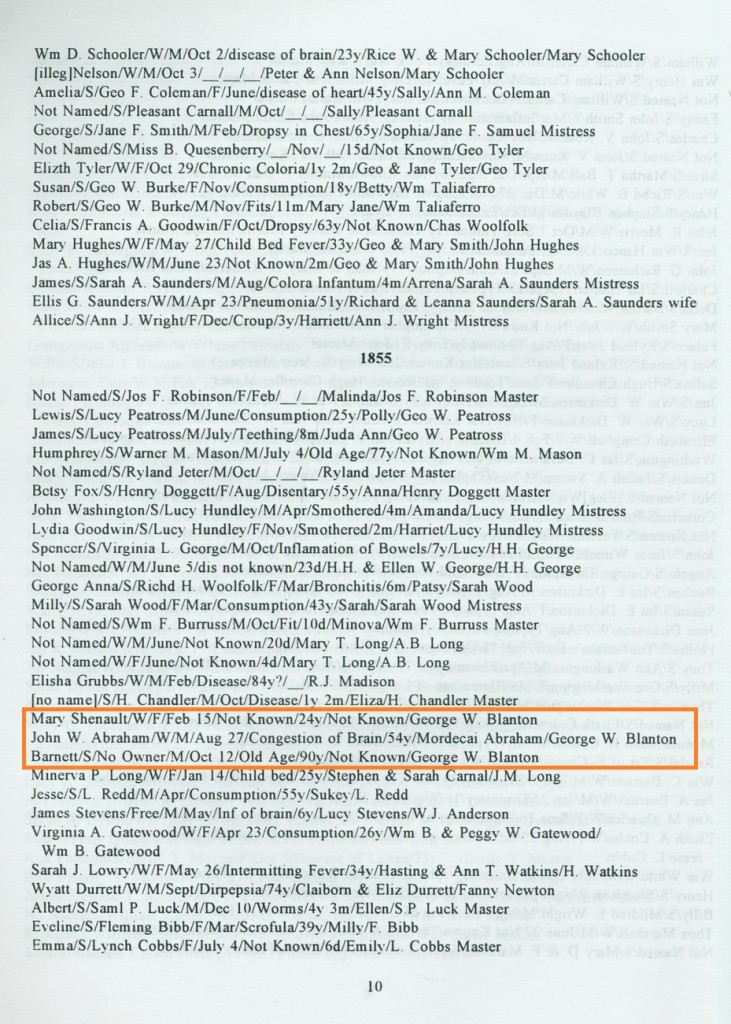

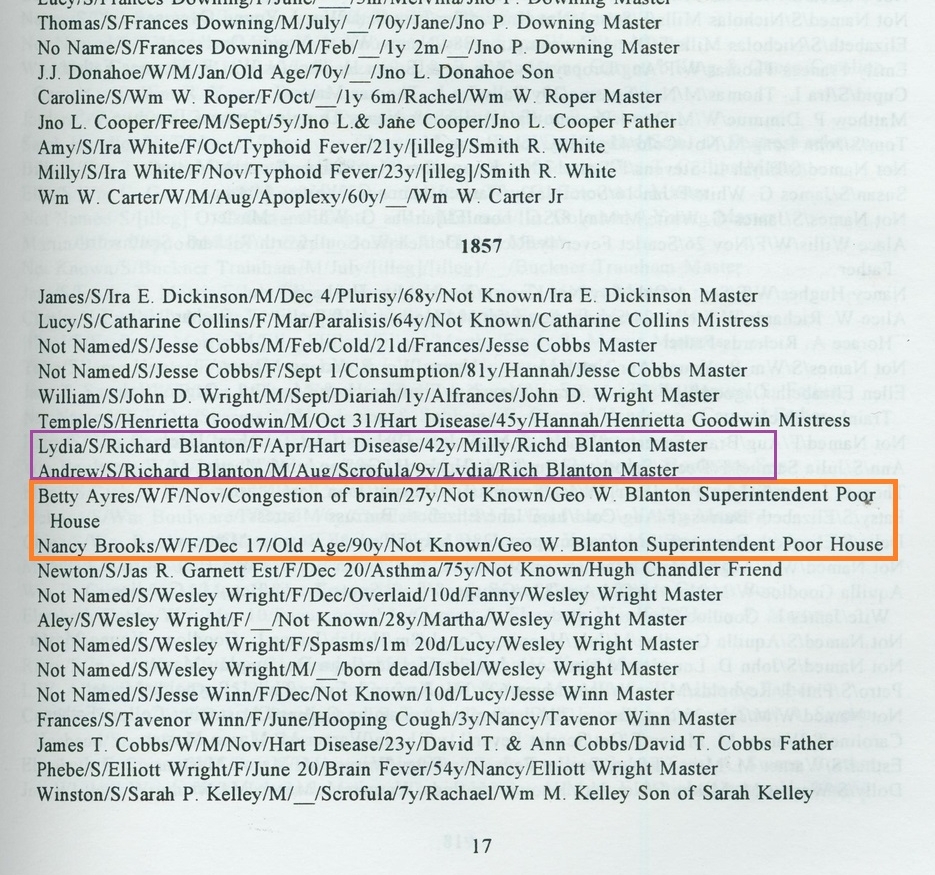

On page 10 of the index, I wondered why George W. Blanton would have reported three deaths in a row of people to whom he was not related (the last name on each row is the reporter).

The first name on each line is that of the deceased. The second to last name is that of the parents, if known.

A few pages later, George’s occupation (see the orange section) was included in a report and I learned that he was the superintendent of the poor house. All kinds of images running through my mind with that tidbit.

Look at page 17 above, again. When there is only a first name for the deceased followed by “S”, that means the individual was a slave. According to the index legend, the second name listed is the slave’s owner. Now, look at “Andrew’s” age. The fact that a 9-year old can be considered a slave isn’t nearly as repulsive as the 2-year olds and the 6-day olds who were also listed as slaves. The one positive is that, if known, the slave’s parent was listed, which makes some genealogy research possible.

On the next page, I saw a name I recognized, that of Lucy Blanton. Because of this entry, I now know her maiden name and her parents’ names.

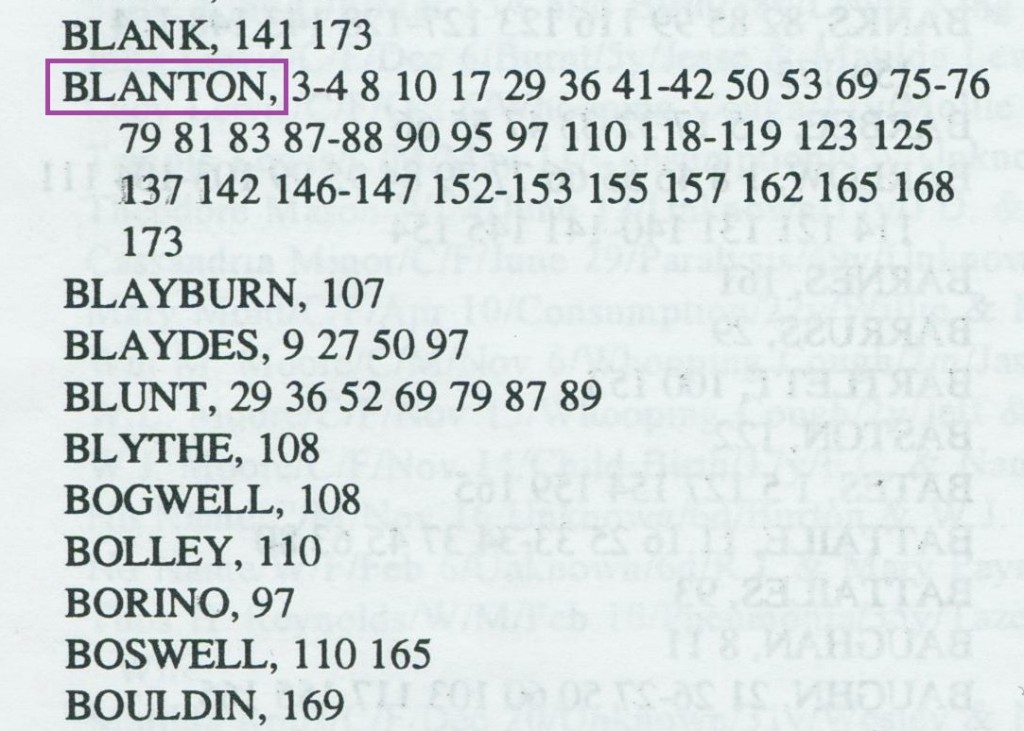

By using, the index in the back, I was able to transcribe the entry for every Blanton.

Go Online: The other great thing that most libraries have to offer is free online access for their onsite patrons to genealogy sites, such as Ancestry.com, MyHeritage, and Fold3. They may have local newspapers on microfilm, historical maps, and cemetery indexes, as well.

Start Writing: I may not be able to tell what an ancestor had for breakfast after visiting my Local History reading room, but there is so much that I can learn about them. One of these days, I am going to find a relative in someone’s diary or family narrative or in the “Who’s Who of Hanover County,” but until then, I can start writing my own stories.

2 Responses to Genealogy: Using the Local History Room